SCRIPT – MEMORY

Chaumont-Zaerpour, Heresies, Chris Kauffmann, Fernanda Laguna, Jordan Lord, Tiphanie Kim Mall, Rietlanden Women’s Office, Niklas Taleb

13. April – 14. July 2024

Opening 12. April, 6 pm

SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Fernanda Laguna, El Encuentro, 2022, in SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Jordan Lord, I Can Hear My Mother’s Voice, with Deborah Lord, 2018

White light is reflected in an abstract pattern on gray blue water. A caption over the image reads: “That's beautiful”.

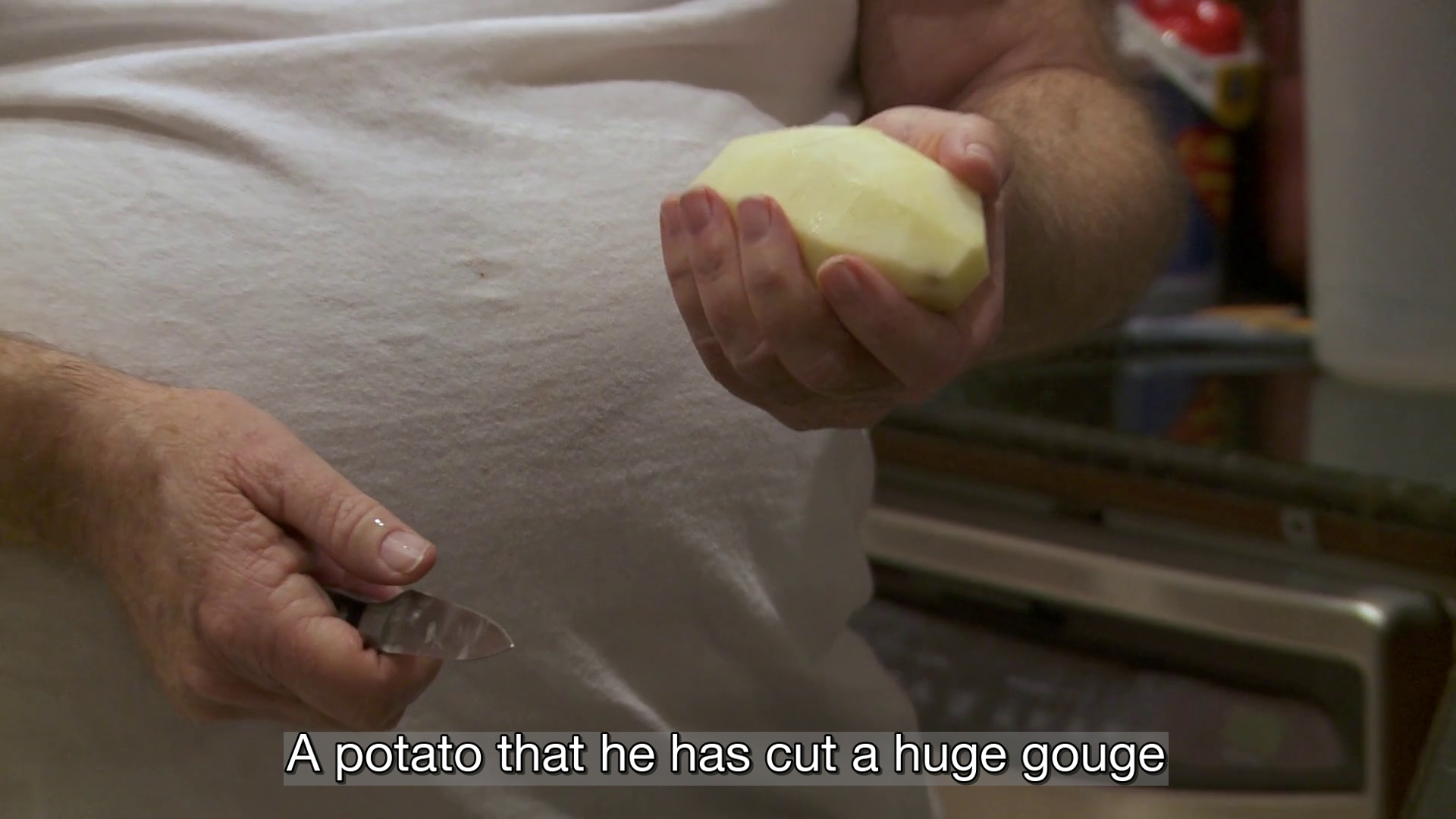

Jordan Lord, I Can Hear My Mother’s Voice, with Deborah Lord, 2018

An older white man holds a peeled potato in one hand and a knife in the other, wearing a plain white t-shirt. A caption over the image reads: “A potato that he has cut a huge gouge”.

SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Fernanda Laguna, Corazoncita, 2022, in SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Chaumont-Zaerpour, Panorama, 2024, in SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Chaumont-Zaerpour, Panorama 2, 2024, in SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Chris Kauffmann, CallMeChris Archive (2012 – 2015), 2023 / Chris Kauffmann, Atlas, 2023, in SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Chris Kauffmann, CallMeChris Archive (2012 – 2015), 2023

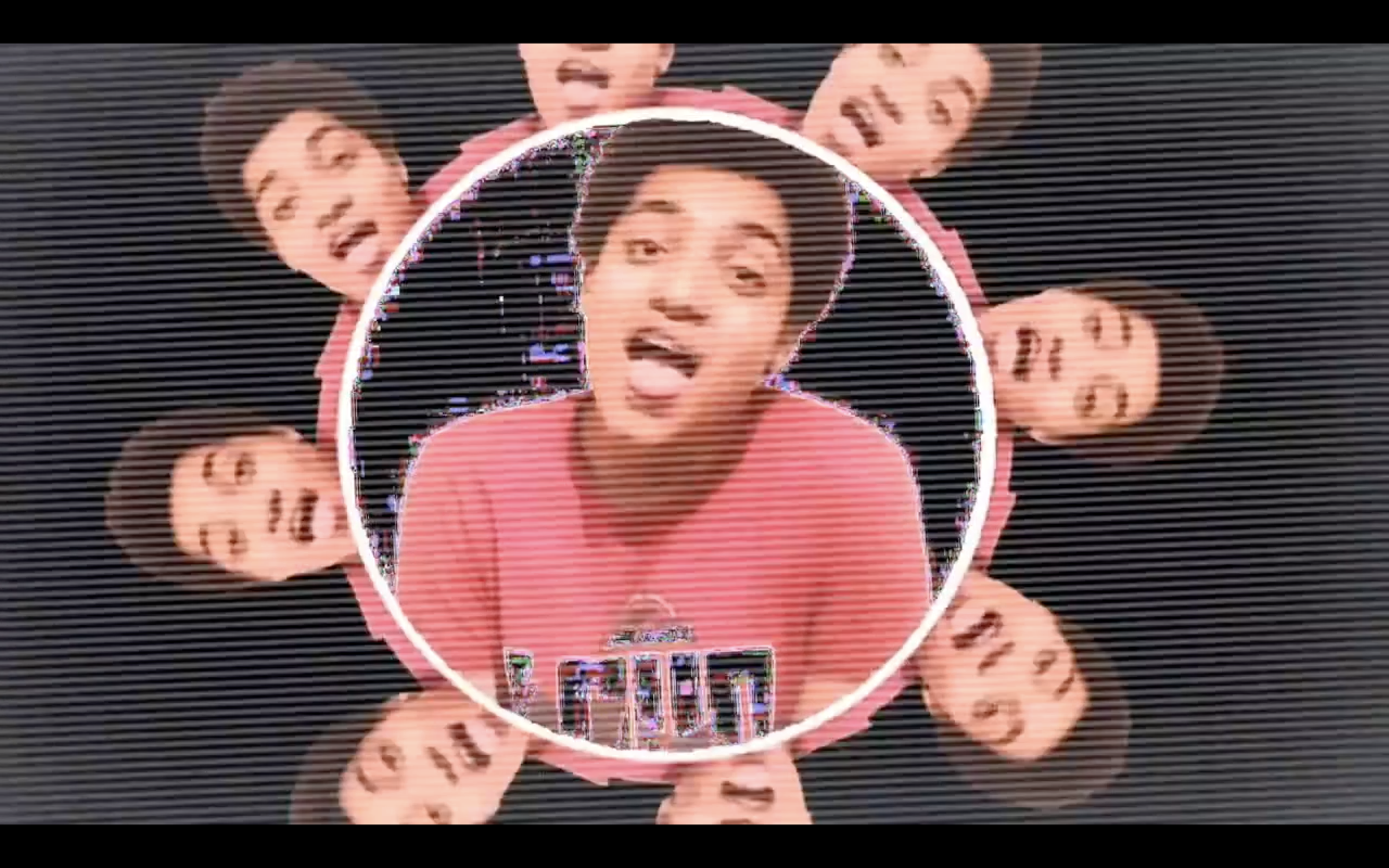

Niklas Taleb, Reverse Psychology, 2020, in SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Tiphanie Kim Mall, Schwester, 2021, in SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Tiphanie Kim Mall, Schwester, 2021

Rietlanden Women’s Office, Printworks, 2024, in SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

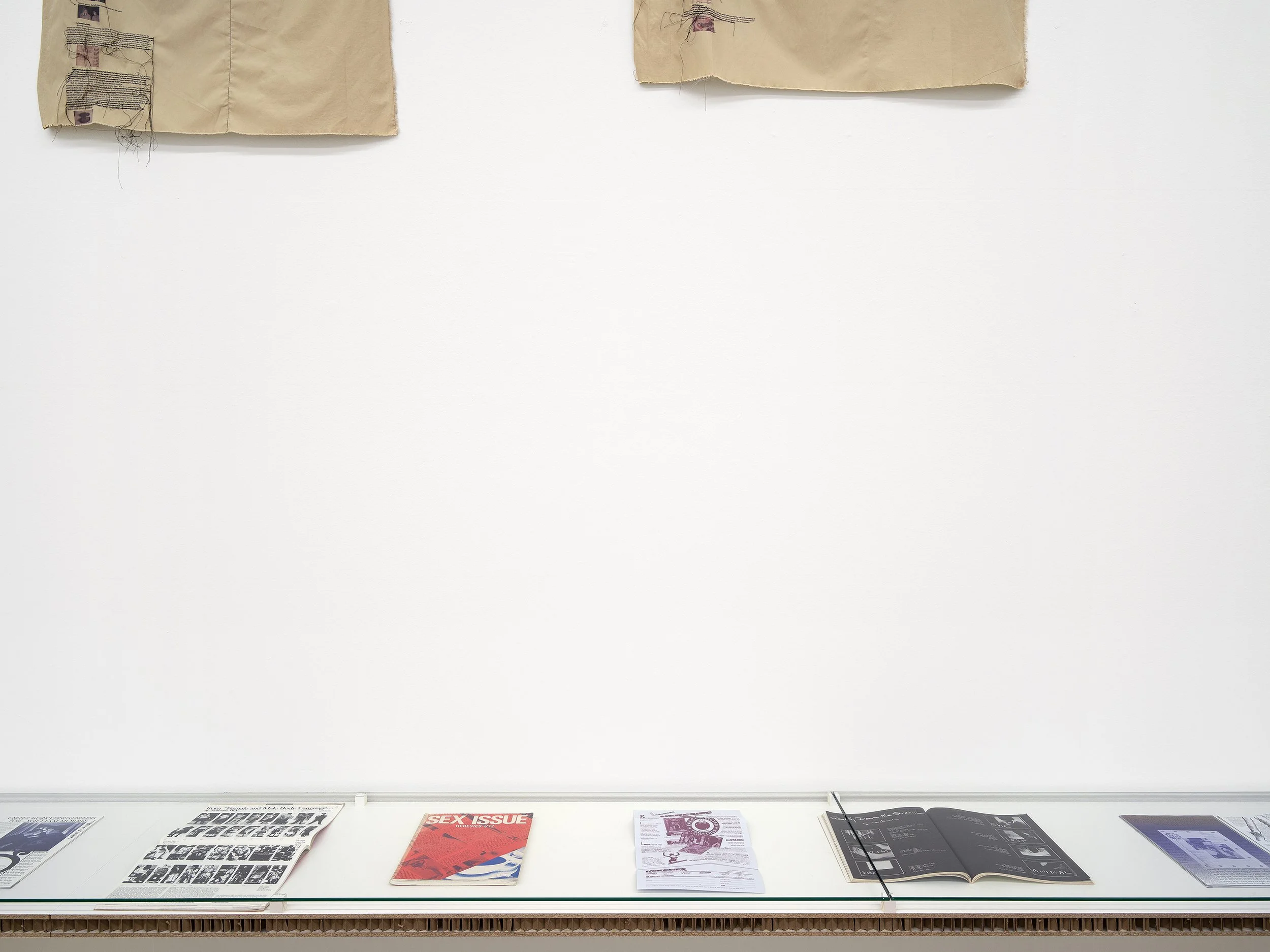

Rietlanden Women’s Office, MsHeresies, 2018–2022 / Heresies Collective, HERESIES, 1977–1993, in SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Rietlanden Women’s Office, MsHeresies, 2018–2022 / Heresies Collective, HERESIES, 1977–1993, in SCRIPT – MEMORY, Kunsthalle Winterthur, 2024. Photo: Cedric Mussano

Playing it by the book is a necessity of our social contract. It is also its bane. We meet, greet and are in touch – the success of which is based on common codes. As a child you begin to abide by a script, rehearse, learn it off by heart. The script includes your “we”, the people in your immediate and not so immediate surroundings, and you become with them, are familiar, repeat. Securing the ego (which does not necessarily mean security of the ego), the return to the known, is at the core of this repetition. Craving an entity that reinforces and embalms leads to automatisms, and the most subtle but defining mechanisms of reproduction occur – gesture, rhetoric, tone. Memory is cunning, it clouds recollection in the soft padding of comfort. It’s a fuzzy space in the mind between reality and fiction. Joan Didion writes: “Time passes, memory fades, memory adjusts, memory conforms to what we think we remember.” The sense of connection to places and people that is so essential to memory is constantly recalibrated, upholding an understanding of common experience.

“Still, much just will not fit the bill!” A loss of control could and perhaps must be a mode to counteract such tendencies.

The works in this exhibition express the need for a gesture toward a loss of control in order to overcome one’s own being in the world. They set a stage for a scriptless act, bound by and fraught with (mis)understanding that could potentially change memory’s course. Key is their conception as tool: Many artists include people they are immediately surrounded with and at times rely on or who rely on them – family, friends, acquaintances. They work with their personal histories as a way to think about involvement, to share the process of making meaning, and to shift the dynamic between author and subject, steering away from making alone, from within oneself, which is still understood as the uncompromised creative process per se. In this they practice a loss of control, letting others define how the work develops with them, in turn redefining their own role. They frame themselves whilst framing others, troubling the idea of the artist as sociologist. Pierced with the emotions of being in close contact, the works’ conceptual frameworks include formal glitches that stress how memory – and the capture of the stories that play a part in the formation of it – is subjective and partial but also always some mirror of reality. The artists of these works hand over the camera, incorporate articulation of others and document everyday life. They include framing and filtering devices to double (who is telling the story?), blur (it is only part of the story!), and defamiliarize (you can make up your own mind about it.), always moving between immersion and detachment.

On a larger scale, relatability is at stake. There is much talk of collaboration, of the longing for and necessity of community. But what is actually in play in a practice involved with others, especially those we are already in community with? A veneer of consensus cracks under little pressure. They meet, and it becomes clear that they may not understand each other. What happens when the underlying assumption that it is so difficult to work together is an underlying fear of losing oneself? After all, a loss of control can be frightening, embarrassing, confusing. Often, feeling restricted by others is followed by the awkward and uncomfortable state of reacting by default. Whatever it may seem, the conflicted teenager still likes to rear his head. Bouts of longing for symbiosis and reassurance are paired with the fear of being compromised. The latter, as protective behaviour, clearly represents a loss of control and may be a condition too precarious; the question here is not where it comes from, but where we find ourselves again in the jumble of narratives.

The works, awakening moments of surrender, of letting go and letting in, are parables for the cultivation of community in a time of ever-more predictive strategies for the avoidance of risk. It is no coincidence the works often point to contexts and histories that did not automatically belong, in which banding together so as to portray and perform the same language was and is requisite. The exhibition proposes a politics of participation rather than representation, in which the artworks are understood as one part of a process of translation among a group of people. Keen to bring the unforeseeable into the equation, it marks the beginning of thinking about Kunsthalle Winterthur as a space of involvement.